By Jay Innis Murray

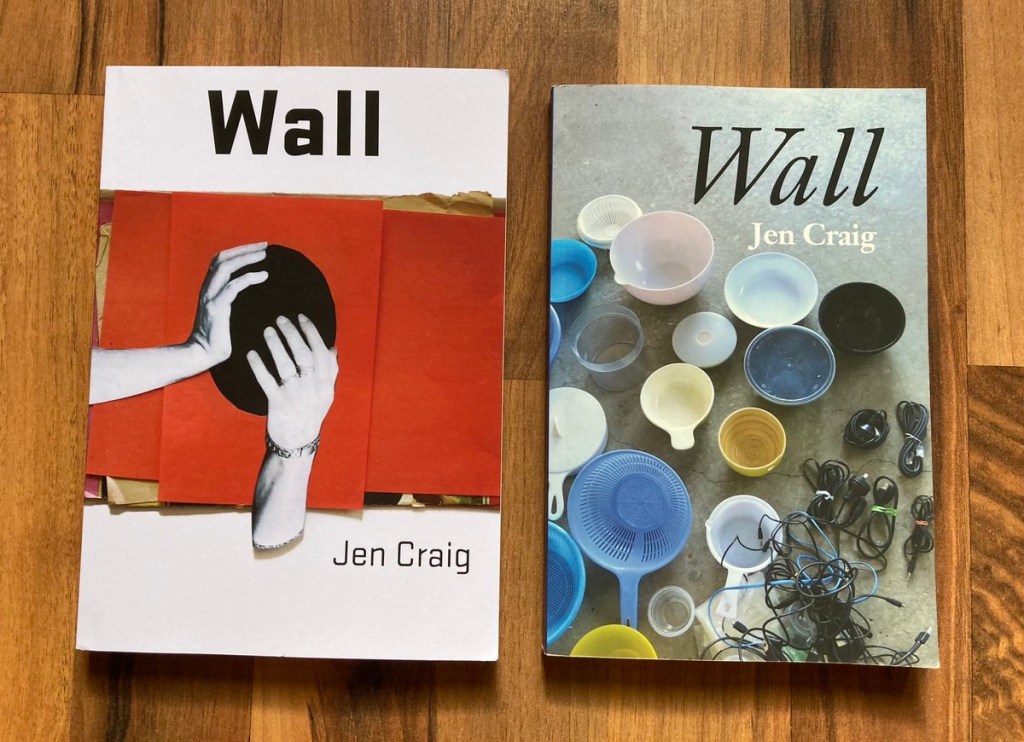

Wall by Jen Craig from Zerogram Press

There was never a moment when you thought you had started on the section of the manuscript where the real part began.

– Jen Craig, Panthers and the Museum of Fire

… all that inner space one never sees, the brain and heart and other caverns where thought and feeling dance their sabbath…

– Beckett, Molloy

It can be startling when your gut reaction to a reading experience is to think of another book that is not much like it. “Not much like it until you unpack what’s going on in your own mind,” it would be better to say. Several years ago, I read Nancy Milford’s 1970 biography of Zelda Fitzgerald. When I got to the end of Zelda, I felt as if I’d taken a long and exhausting hike on a steep and hazardous mountain trail. It was draining. Zelda Fitzgerald had a complicated personality. Milford’s book is a triumph of showing how Zelda thought and what things obsessed her thinking and writing. Since it was a biography, it revealed lots of details second or third or fourth hand.

Jen Craig’s third novel Wall has a first-person narrator, but the book is as studiously devoted to truth-telling as the best biography. It is dedicated to telling no false thing. Presented as a document the narrator is writing down for her partner, Teun (the narrator is in Australia while Teun is in London where they live), the telling circles around events previously told to Teun with various levels of completeness. Where past telling may have been tainted by omissions or distortions, the document (the book the reader holds in her hand), is an effort to make up for it. It has a deep, philosophical intent. The narrator is likewise concerned with attacking the confusion she feels about how others think of her, what she calls “second-hand versions of me.” This novel gives the reader one of the best depictions of thinking in fiction that I have read in a long time.

The plot of the novel does not unspool in linear way, but it is not especially complicated. The narrator has come home to Australia from London after the death of her father. She is an artist. She did not come home in time for her father’s funeral due to a rare-opportunity gallery showing of her artwork. She has come to Dad’s house, however, to deal with the mess of it. It is filled with a lifetime of hoarded messes (things like papers and wires and boxes full of the junk of conspiracy-minded projects her father abandoned over the years but never tossed out). They are mostly ordinary objects. They are notable only as a collection of material.

Before leaving London, the narrator states to her former art school mentor Nathaniel Lord that she has an idea to use materials from the mess in the house for an encyclopedic, suburban Sydney installation project in the manner of the artist Song Dong.

The historically specific installation Waste Not by Song Dong is a touch point for the narrator. You can view a page about the 2012 showing the narrator attended here.

https://www.barbican.org.uk/whats-on/2012/event/song-dong-waste-not

The level of sincerity of her discussion of the project with her old mentor and, indeed, the sincerity of her intention to complete a similar project from her own family’s past (through the objects that remain) is one of the questions the narration circles around. The possible project is one of the visible stars of a constellation of concerns or topics. It would be useful to have a diagram. It’s possible a wheel pattern with spokes would be even better. At the hub of the wheel would be the house and Sydney, Australia. Spokes out from the house would include Song Dong and his project, the narrator’s parents, her sister Leah, the narrator’s own anorexia, and art school. From the art school hub, you’d have spokes to her friends Sonya and Eileen, her rising art career, and her mentor Nathaniel Lord. From Nathaniel Lord, you’d connect London and Teun. While I claimed the plot is not complicated, the style can be. The narration will leave a subject only to pick it up again, repeat many of the same facts and feelings about it, add a new fact or complication then move on again, much like the restless mind will do.

You can feel the narrator’s honest grappling with the past and the resentments and feelings of envy that still exist between her and her art school friends in the way she rehearses future conflicts and revisits past conversations with the torturous thoughts of things she could have said or should have said. Ways things could have been said better or with more devotion to accuracy. Defensive about an issue early in the book, she may return to it later, as she types the words in the document to Teun, from a new angle and with fresher insight. “That is,” she writes, “continuing a long and obsessive thought to its logical conclusion.”

My favorite parts of the book are about the lasting art school between the narrator and her friends Sonya and Eileen. Sonya’s strong personality develops some of the conflict in the book, and the narrator’s attempt to help Eileen in her family situation gives the narrator a Kafka’s Castle-like ride in a junk car that lends inspiration to more circles and circles of thought.

The novel approaches a Proustian insight that social life (how we exist for others), our own thinking about ourselves (and how that rapidly or slowly shifts), and the writing of novels can all do the same work. There are versions of us. We present them. We impersonate them. We even encounter versions of ourselves we might not recognize or believe in.

These various versions of me that you are always so keen to deflect as soon as I repeat them. It having been impossible to make you understand how I feel about these second-hand versions of me, since my confused feelings must be so hard for you to listen to, as well—impossible, too, since along with your justifications and dismissals of everything you think has distressed me, you have your own version of how I am that takes no account whatsoever of how evasive I can also be. Yes, there are many years of abject evasions—my whole life, as it seems, intent on evading, and in fact succeeding in evading, what should probably be fundamental to my being as a daughter and a friend. (page 170)

That fundamental thing, does it even exist? Like a great biography (another version), a great novel gives us access to the work of finding out. Writing one’s own life might just be “Concocting this realness as I speak,” as the narrator offers. “This other layer of fiction.” Jen Craig works in the tradition of Thomas Bernhard and Beckett and other greats of the middle part of the 20th Century. It’s not a small claim, but I’d feel the desperation of a losing side if you asked me to refute it.

Leave a comment